The Class Divide in Education

A Taxonomy of Class Power in Our Industry

This is the introduction to the upcoming second edition of our text, The Industrialization of Education. It lays out our general analytical framework.

Two ideals are struggling for supremacy in American life today: one is the industrial ideal dominating through the supremacy of commercialism, which subordinates the worker to the product and the machine; the other, the ideal of democracy, the ideal of the educators, which places humanity above all machines, and demands that all activity shall be the expression of life. If this ideal of the educators cannot be carried over into the industrial field then the ideal of industrialism will be carried over into the school. Those two ideals can no more continue to exist in American life than our nation could have continued half slave and half free. If the school cannot bring joy to the work of the world, the joy must go out of its own life, and work in the school, as in the industrial field, will become drudgery..

It will be well indeed if the teachers have the courage of their convictions and face all that the labor unions have faced with the same courage and perseverance.

-Margaret Haley, “Why Teachers Should Organize,” 1904 speech to the National Education Association convention

Industrial Ecology

America never deindustrialized. It just scaled down its industries in the manufacturing sector of the economy while concentrating industrialization in other parts of the economy—like education. We must expand our concept of production beyond the factory floor if we’re to ever have any hope of understanding ourselves and our situations as workers. Education is an industry with the same exploitation and disparities of power, privilege, and resources as any other. It has transformed from local, community-based schools to an industry in the same way the retail, service, logistics, legal, healthcare, hospitality, railroad, construction, maritime, agricultural, and other industries have. A critical inspection of the history of American education reveals how corporations, politicians, and a Public Boss Class guised as ‘the voters’ have designed schools, libraries, archives, museums, and research facilities as factories. Factories that extract profit from education workers and students.

Our analysis of the education industry draws from the investigative framework of workers’ inquiry. Workers’ inquiry takes up tools honed by the social science disciplines, such as sociology, history, and economics, to analyze capitalism—but grounded in Marx’s critique of capitalist social relations. What “set worker’s inquiry apart from…other empirical studies was the belief that the working class itself knew more about capitalist exploitation than anyone else” (Mohandesi 2013). Studying ourselves can bring “an exact and positive knowledge of the conditions in which the working class—the class to whom the future belongs—works and moves” (Marx 1880). Since we are a collective of workers subjecting our own industry to ruthless criticism, we prefer to use the term worker’s self-inquiry. Educators know the landscape of our industry better than anybody else. Yet, our collective knowledge is fragmented. The education industry is vast, diverse, and global. If we want to understand our sorry situation while charting a course towards liberation for ourselves and our communities, we must answer some essential guiding questions:

What is an industry? What is industrialization?

What comprises the education industry?

How does the development of capitalist industrial production impact work processes and institutional structures in education?

What does non-industrialized education look like?

What is capital? And what is capitalism? How do we analyze class in the 21st Century?

In education, who are the workers? And who are the bosses?

We’ll deal with the last question first. Among the workers we find janitors, bus drivers, teachers, paraprofessionals, interventionists, sports coaches, librarians, substitutes, adjuncts, graduate workers, docents, food service workers, library techs, social workers, and clerical staff. Among the bosses we find administrative bureaucracies like the Department of Education, charter school management companies, school boards, and distant education corporations like Scholastic, Pearson, or Great Minds. Principals, assistant principals, deans, instructional coaches, library directors, museum directors, and other administrators form a managerial middle-class.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably a worker. This text is for all education workers—whether you’re a school nurse, on maintenance staff, a security guard, a library associate, a clerical worker, or whatever else. If you work in a place engaged in education production, this will hopefully help you analyze your corner of the industry in a broader framework. But we encourage others to reach out to collaborate with us, and to write their own inquiries into the industrialization of more specific educational sectors.

Future inquiries could include detailed taxonomies of specific, local educational systems. Where are the schools, the libraries, the museums? Who works in them?

How are workers already acting collectively to build power and resist capitalist domination? What divisions exist that bosses take advantage of? How can we intervene to organize with other working-class folks while countering division with solidarity? Look up and look around! Leave nothing unexamined, if you can. And write it down! We need to analyze and discuss our experiences collectively—as worker-intellectuals, not as “professionals” or academics.

We oppose capitalism—a system where the means of producing what humans need to survive and thrive are owned by a variety of private and state entities—entirely. The vast majority of humanity is excluded from any real acquisition of private property. Some of us may “own” houses, but until you pay off the mortgage after multiple decades (if you can ever pay it off), the bank is the real owner. During those years, the bank can foreclose your house if you fall on hard times. And access to that privilege of homeownership is being moved further and further out of reach by gentrifying development firms. That leaves us dependent on working for a wage or salary to survive, forcing us to accept whatever despotic workplace relations our bosses impose.

Capitalism cannot be reformed—not for long, at least. It is a system that relies on the movement of capital to produce economic wealth. Capital comes in two forms: money and commodities. The money form is just that: money, including bank deposits, hard cash, and other liquid assets. The commodity form includes resources that can be bought and sold on the market with money. The role of capital is to bring the labor power of workers from lots of different places together to generate unprecedented wealth. This wealth is produced collectively—by billions of workers around the world.

Humans are inherently social. This applies in our workplaces just as it does in every facet of our lives. Our ability to cooperate is fundamental to the development of production and the accumulation of wealth. It allows the economic specialization by job role—the division of labor—which lies at the source of modern wealth creation and industrialization.

But that socially created wealth is not distributed equally. Instead, the employer, whose only use is that they have more money than everyone else, takes the product of workers’ labor and sells it for a profit. Only part of that profit ever goes back to the worker. For the factory owner, the restaurateur, or the school board member, the impulse is to pay workers as little as possible while extracting the maximum labor. This is exploitation. All profits are effectively unpaid wages. Bosses squeeze more surplus value—time spent working more than you’d need to survive—out of the workers by reducing wages and lengthening work hours. Or by making those hours more intense and demanding.

Rather than playing a positive role in developing the productive power of societies, capitalist “leaders” suck up the surplus produced by the endless ranks of workers of various backgrounds. Employers ultimately add nothing. In fact, even the means of production they own, like physical buildings and machines, were all made by workers, too! Only workers possess the physical and mental ability to create wealth, while the employers only have the power to control the relationships within productive processes. Private ownership and profit ensures that socially created wealth is managed in chaotic and destructive ways (Foster 2011) (Collective et al. 2023). Capitalism’s emergence as an economic system was never the only way to achieve socialized, modern, industrial production. Its eventual rise to dominance was historically contingent, meaning it has always competed with alternative methods of production that it has beaten out (Federici 2004). Up till now, at least.

Big capitalists—corporate executives, banking magnates, and Wall Street traders—are less than one percent of the population. But they call all the important shots, though most of them haven’t worked in any of the industries they own shares in. Surrounding them is the middle-class. People use that term sloppily in America. Often, they’re referring to anyone with a college degree, or any degree of comfort or social standing. Middle-class seems like a cultural mindset rather than a coherent class. There is, however, a concrete middle-class. They’re the small business owners, small fry landlords, preachers, and professionals such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, administrators, scientists, and principals (AngryWorkers 2020). These folks usually place in the top fifteen to twenty percent of the economy. The rest, 80 percent, is the working class and lower strata of the poorest in our society like the homeless.

Supporters of capitalism usually reply that capitalists provide the machines, facilities, and tools. Who built the machines and buildings? Who crafted the tools? Workers did. Machines “copied the artisan’s physical movements and transferred it onto an apparatus, such as the weaving loom or the spinning machine. Major investment was necessary for engines to move these machines, while workers who operated them could be paid much less…and the independent artisans died a rapid social death” (AngryWorkers 2019).

Capitalists rely on workers at every step of the production process. None of it moves without them. Yet, the power of workers cooperating in huge numbers adds to the power of their employer—a power that has opposing interests to those of workers— rather than the well-being of themselves and their communities. Our ability to cooperate, the core source of industrialization, comes to our employers for free.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of the skills, attitudes, and discipline that enhance this ability to cooperate at work are given to us by societies that absorb these costs through public education or the family. Or we have to pay out of pocket for them. The large, mass workforces adapted to the strict authority of workplace bosses and routines had to be created over the last few hundred years. Education plays a key role in this process by serving as internal clockwork machinery that manufactures and regulates the pace of life under capitalism. It marks “the passage of progress, a time without frontiers” (Bennett 1995). None of this comes at a cheap cost.

By passing these massive educational investments off to society at large, capitalists have been able to drastically lower their labor and operation costs. A sliver of the hard work that individuals put into their education, the tuition paid, and the resources expended by the broader society is returned to the finished product—the worker— as a modest pay premium. Our own innate ability to learn is thus turned against us.

Another reply is that capitalists take on the financial risk of owning the operation. Who dies when the machinery catches a stray hair or the employer refuses to follow covid protocols? Workers! Who loses when privatized schools without proper oversight fail? Workers and students! We build the whole world with our combined labor. But capitalists use industrialized production to steal our labor and our time for their own private profit. We must recognize this monstrous system for what it is, and organize to overthrow it for the sake of all humanity.

Whether we like it or not, the pandemic revealed just how desperate our situation is. We must look that reality in the face and organize. School, library, and museum administrators harangue us for every mistake and expect us to do more with less staff and funding. Stories of assaults against staff in educational facilities are proliferating as the American Empire’s social fabric deteriorates. Meanwhile, corporate profits in education keep growing.

Industrial Taxonomy

An industry is a collection of production facilities, companies, job roles, and pieces of infrastructure assembled across a geographic area to produce a common set of goods and services. Every industry encompasses three main layers: production, distribution, and consumption. Through these layers, industries interact with each other. Workers in a factory don’t usually do distribution. Instead, shipping industry workers at Amazon, UPS, USPS, and FedEx bridge the gap between producer and consumer. The printing and publishing industry manufactures textbooks, encyclopedias, and other texts for the education system. The tech industry produces computers, tablets, and digital tools for schools, libraries, and museums.

Industrialization occurs when an agricultural society changes into one where a minutely crafted division of labor, huge urban populations, and the application of technology allows for mass production of goods and services. Four conditions are needed for industrialization to occur:

A centralized workforce practicing division of labor. Tasks must be divided into the smallest possible units. Labor is also divided along lines of gender, race, type of work (blue collar versus white collar), and geographical location.

The subjugation of workers to the machinery they build and operate. Capitalism is a fundamentally despotic system now reliant on huge sets of machinery. Workers add to these masses of machinery with every productive action, yet in their relationship with the machine they occupy a subservient role. The machinery becomes synonymous with the power of capitalist investment, when the real origin is the sweat and blood of collective labor.

Primitive accumulation. Also known as initial or background accumulation, it’s an ongoing process that destroys other, competing political and economic systems. By sifting through the wreckage, capitalists can absorb more labor and resources. Marx described this as beginning with the “enclosing” of land that threw the peasants into the cities. Slavery and colonialism continually grease the wheels up to the present day. The fledgling industry of Early Modern Europe, for example, was mainly fed through imperialist looting and enslaved labor (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture 2003).

Production must become increasingly consolidated in fewer hands. Early Modern merchants and landowners tied disparate, small to medium sized production units—like cottage industry—into massive ones. Eventually, they generated enough capital and productive capacity for the emergence of large, monopolistic firms. Such firms can effectively circulate commodities on a national or international scale. By exploiting workers and driving down costs throughout this process of circulation, those who have money to invest accrue capital (Marx 1867).

We can sort the economy into six distinct categories. These are: agriculture and fisheries; mining and minerals; general construction; manufacture and general production; transportation and communication; and public service. Every industry falls within these broad categories. Education workers under public service. Blue collar or white collar— which loosely describes what type of work you do—has little relevance. Rather, we should categorize on lines of production, distribution, and consumption. This way, we can lay the foundation for a worker/student run, democratic education industry.

What exactly comprises this education industry we need to organize? To figure that out, we must deduce its main products. Education plays a key role in the accumulation of human capital: the built up knowledge and skills that make a workforce productive; and has since capitalism’s earliest days. The production and circulation of human capital manufactures a person who has been inculcated with the knowledge, ideology, discipline, and culture that primes them to serve the whims of business owners and politicians. And to do it all according to the grand, invisible clockwork machinery that sets the frenzied rhythm of capitalist life in motion. Education also serves as a connecting point—a node—between different industries and social groups with varying levels of power.

Nursery workers, nannies, au pairs, stay at home parents, babysitters, and education workers share the burden of carrying our society across generations. Libraries, museums, and schools are constant, essential sites of family events and social services. Schools free up millions of people for full time work. Museums help reproduce knowledge and civic traditions. How could anyone possibly untangle all these threads and emerge with anything useful to working people? The class composition of education workers is diverse and ever-changing, as are the structures of the institutions that employ them. But by studying the "ongoing interplay between the articulations of labour-power produced by capitalist development, and labour’s struggles to overcome them" (Conatz 2011), we can draw some conclusions. With that in mind, the education industry includes:

Public, charter, and private pre-Kindergarten through 12th grade schools.

Post-secondary institutions like colleges, universities, and trade schools.

Libraries and archives, including: public library systems, academic libraries at universities and colleges, school libraries in K-12 schools, and special libraries like presidential library museums.

The Exhibitionary Complex of cultural institutions like museums, exhibitions/expositions, and heritage sites.

Non-profits, foundations, and government departments geared towards education research, funding, and curriculum development.

Corporate and government job training and lifelong learning facilities.

The amorphous armies of gig tutors and tutoring companies that surround the entire industry.

Educational Technology (ed-tech) firms.

Even though educational facilities are not literal factories, workers in the industry carry out acts of production constantly. That includes lesson planning, building construction and maintenance, sorting museum collections, classroom setup, food service, library program creation, and teaching. In the process, these workers use tools developed by educational non-profits, foundations, government departments, and private companies. Recognizable examples include textbooks, computers, learning standards, classification systems, proprietary curriculum, standardized tests, databases of information, and digital tools. Tools they had no say in making. And with little to no control over how or when they use them. Together, us workers contribute to the development of pedagogical machinery that our bosses use to dominate us and extract surplus labor value. Pedagogical machinery shapes the raw material—students and patrons—into the workers, managers, and owners of the future.

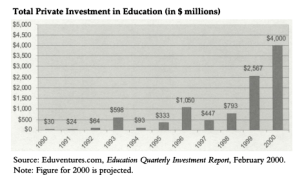

The industrialization of education began in the 1840s. Since then, businesspeople have used politicians to structure education along the lines of private industry. Under the guise of ‘reform,’ these succeeding generations of ruling class capitalists—from factory owners to startup bros—have shaped and reshaped education. Since 1992, capitalists have peeled away huge swathes of education from the public sector entirely. The goal is the end of free public education altogether.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed reading this, please help spread the word.

Get in touch!