The Industrialization of Education, Part Two: Schools in the United States, 1840-1930

Class struggle has been a defining feature of education under capitalism since its earliest days. We're tracing this history by analyzing multiple educational sectors, starting with K-12 schools.

Some Updates

The collective and its fellow travelers are hard at work producing workers’ inquiries of educational workplaces in the Washington, D.C. region of the United States. While you wait, we wanted to publish updated versions of our overall industrial taxonomy of education that elaborate on our original thoughts. Building on the introduction to the series: “The Class Divide”, we delve into a history from below of K-12 schools in the United States.

The Industrialization of Education, Introduction: The Class Divide

This essay is the introduction to an upcoming series on the history of education through the lens of capitalist social relations and industrialization.

After these entries on K-12 schools, you can expect pieces tracing the historical trajectories of libraries, archives, museums, colleges and universities, daycares, educational non-profits, government departments, expositions, and vocational facilities. This will be a series without a definite end of any kind, one that will grow with our expanding collective knowledge of the subjects at hand. If you’re interested in following along, give this post a like, a restack, or both! For those who aren’t already subscribed to By and for Angry Education Workers, please consider subscribing!

Even better is to share this, or any of our other pieces, with coworkers or comrades you’re organizing with outside of work. Our goal is to root ourselves in working class lives and collective struggles, which means engaging in dialogue with fellow education workers of all backgrounds.

Please also consider filling out our reader survey. This survey helps us to get a very general sense of who you are and what you are interested in seeing more of from By and for Angry Education Workers.

Finally, we’ve been steadily accumulating a trove of research resources about the education industry. If you’re interested in helping us add to this collection, follow this link:

The industrialization of schools in the United States began in the 1840s. Since then, business owners have used politicians to structure education along the lines of private industry. Under the guise of ‘reform,’ these succeeding generations of ruling class capitalists—from factory owners to startup bros—have shaped and reshaped education. Since 1992, capitalists have persuaded politicians to privatize large swathes of the K-12 school sector. The goal is the end of free public education altogether.

The Early History of Education in America

Pre-industrialized education looks like the one-room schoolhouses of American legend. Or the small community schools taught by ministers in the New England colonies. Tribal communities around the globe pass down knowledge and traditions in communal, but informal ways. Preceding industrialized library systems, there were private subscription libraries for elite European men (Hillary and Abbott 2015). The first museums were the private collections of rich people, who began to selectively display them as “cabinets of curiosity” in the 1500s (Bennett 1995). We’ll examine some of these in more detail in future essays tracing the specific histories of libraries, archives, and museums.

Dorchester, Massachusetts opened the first taxpayer funded school in 1639. Massachusetts Bay, along with most Northeastern colonies, passed compulsory attendance laws in 1642, and required parents to teach children how to read (Goldstein 2014) (Easterling 2013). But education was not an industry yet—it could not be. The earliest rumblings of industrialization were still barely felt, even in textiles.

Early school systems were scattered, community oriented, local in scope, and taught by ministers, not a dedicated teaching workforce (Goldstein, 2013). Yet, primitive accumulation in education was underway. Spoils from the violent colonization of the Americas had been flowing for hundreds of years, and schools were built on land stolen from indigenous tribes like the Massachuset, Wampanoag, and Nauset tribes with stolen bodies.

Land encompassing what is now Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin—wrenched from the British in the final stages of America’s blood drenched birth—was called the Northwest Territory (Black 2020). These were lands inhabited by native nations like the Delaware, Miami, Potawatomi, and Shawnee, whose homelands were auctioned off by a broke central government to white settlers for free (Black 2020).

Education was bound up in this dispossession. In fact, “the Ordinances placed public education at the literal center of the nation’s plan for geographic expansion and statehood in the territories…Every new town had to set aside one-ninth of its land and one-third of its natural resources for the financial support of public education” (Black 2020, 63). Land and natural resources that be forcibly seized by armed settlers in a succession of endless wars starting during the American Revolution and extending all the way into the early 20th Century.

In 1836, during the days of the Trail of Tears and the expansion of slavery westward, “the nation made an enormous new financial investment in public education. Tariffs, the collection of war debts, and the sale of federal lands generated an ‘unprecedented surplus’” (Black 2020, 69) that the federal government handed to the states. Nearly all the money in the “people’s inheritance” got spent on public education. Public education allowed the white elite to integrate lower class white settlers into a political-economic system that exploited them.

Despite the still localized nature of education, regional teaching workforces had formed by the 1820s. Most schoolmasters were badly paid men with no curriculum. Education reformers of the day, like Harriet Beecher, ridiculed them as drunk, tyrannical, and abusive—though they were likely “less cruel or stupid than frustrated. They were struggling with educational neglect…and lack of funding” (Goldstein 2014, 21). A patchwork labor force like this could hardly be called a modern proletariat. But it formed the foundation for the construction of one.

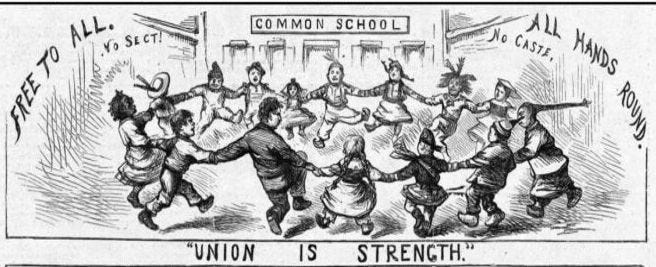

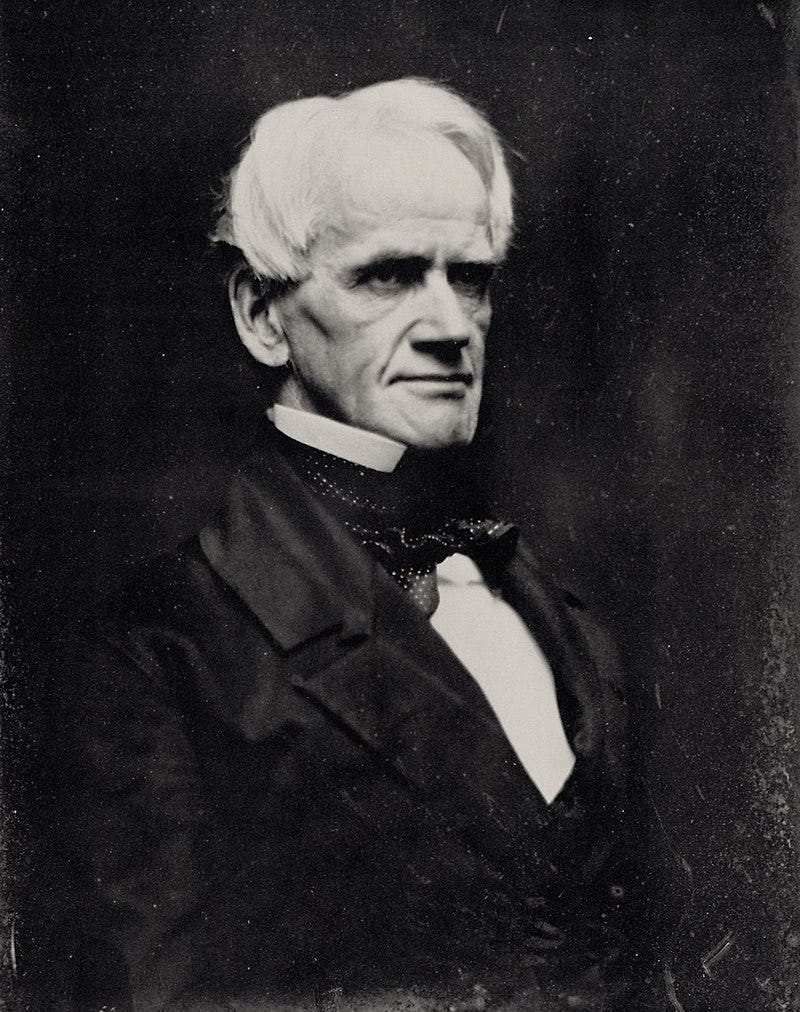

Horace Mann was a Whig politician in Massachusetts with connections to religious social liberals and “fiscally cautious northeastern business interests” (Goldstein 2014, 23). In 1837, he became secretary of the first Board of Education, achieving compulsory schooling for the state’s children. Mann set up the first teacher colleges, then called normal schools, in 1840. There, teachers in training learned teaching as a craft, with standardized practices and subject matters. He only accepted women to save money. As the common schools movement caused local governments across the Northeast and Midwest to build schools, the size of the teaching workforce ballooned (Gross 2018). By 1873, most of these teachers were women (Goldstein 2014).

Now that there were teachers, the question naturally arose: what would all the students learn? Teachers never had any say. Instead, “politicians and business leaders, the kind of men more concerned with educating the next generation of voters and workers than in fostering intellectuals” (Goldstein 2014, 28) held sway over education reformers like Horace Mann and Catherine Beecher. Teachers and schools were “expected to ‘strengthen the moral character of children, reinvigorate the work ethic, spread civic and republican values, and along the way teach a common curriculum to ensure a literate and unified public’” (Shelton 2017, 80).

As teaching became overwhelmingly “women’s work” through the mid-19th Century, teachers simultaneously experienced proletarianization. Most of the women coming into teaching at that time were white and the daughters of poor farmers, blue collar urban workers, or stable middle class families. All these women had few job prospects outside teaching. These women faced patriarchal and capitalist barriers as they sought financial, and, synonymously, legal and emotional independence. Without this material basis for asserting themselves against families, people—especially women—become vulnerable to abusive dynamics. Women moving into the teaching workforce had to navigate these difficulties with little support.

This represents a profound shift at a critical time across an American Empire that was conquering westward at a dizzying pace. Teachers would not be professionals in the sense that doctors and lawyers were (and are). They did not have the ability to self-govern and regulate like genuine professionals had (Goldstein 2014). Instead, they would be workers. American teachers had little say in school operations, pay, hours, or what they taught.

The First Phase of Industrialization in Schools, 1890-1930

School enrollment, along with library and museum construction, spiked after the American Civil War, peaking from 1890-1930. The number of students rose from 12.7 million to nearly 26 million. By 1920, there were over 3,500 public library branches nationwide. Since the end of the Civil War, immigration from the Eastern and Southern margins of Europe, combined with unprecedented industrialization and urbanization, had changed the empire.

A nation of mostly Western European descended protestants treated Catholic immigrants like an invasive species whose illiteracy would hamper economic growth (Gross 2018). Protestant business leaders saw public education as a tool to assimilate them, especially as private parochial Catholic schools sprung up like weeds—sustained almost entirely through donations from local parish communities and outside the bounds of state regulation (Gross 2018). Parochial schools offered a quasi-industrial alternative between the pre-industrial forms of the past and the industrialized models of public schooling of the future. In the 1920s, these parochial schools would accept regulation in exchange for crucial governmental funding, effectively incorporating them into the education industry and marketplace (Gross 2018).

By 1883, the Republican Party had passed compulsory attendance laws in the fourteen Southern states and required Southern states to make education a constitutional right to rejoin the Union (Gross 2018). They wanted the state to use compulsory education as a tool to construct “national growth and unity” (Gross 2018, 64). With a devastated nation to rebuild, compulsory attendance could assimilate defeated Confederates, newly emancipated Black Americans, and recently-arrived immigrants “into the greater body politic” (Gross 2018, 65). Education, then, became part of life, an integral part of the social reproduction process of the capitalist American nation-state.

By the Civil War, philanthropy was well established in education. Charlotte Forten Grimké was a Black teacher and life-long abolitionist who moved from Philadelphia to Port Royal in the South Carolina Sea Islands to teach newly freed Black children. Neither she nor her students received what they needed, so she “wrote to philanthropists in Philadelphia to send picture books for toddlers” (Goldstein 2014, 51). While the common schools movement had tucked most education into the public sector, anti-tax sentiment by business owners left it underfunded. Philanthropy helped the capitalist class put down roots in education on their terms.

Boards of Education hired hundreds of thousands of teachers. Chicago and New York City were epicenters of this expansion. By this time, the Second Industrial Revolution had conjured the juggernaut of capital into being. Mass industry necessitated a managerial class, who cooperated with the rich to enforce discipline.

Chicago was the city on the hill of a “thriving reform scene, driven by innovative ideas in social sciences and progressive politics” (Goldstein 2014, 68). The University of Chicago was the nucleus of this reformist atom. Its president was chosen by the mayor for the school board, charged with “centralizing the curriculum, pedagogy, and administrative structure of the public schools” (Goldstein 2014, 69). Men like him supported Taylorism. They pushed for technocratic management for schools and libraries, with workers and the voters excluded from curriculum policy. Of course, these academics believed they should be the ones making those decisions. Elite academics like college presidents and other administrators “forged an alliance with business leaders, who liked the idea of top-down, expert management of schools, yet deplored paying higher taxes to fund public education” (Goldstein 2014, 68).

Private companies used their political and economic power to siphon public funds and profit off education. Chicago Public Schools had 15,000 education workers throughout the city, which made it the city's largest employer. The government and “professional elites” of the time “reorganized the Chicago public schools and, like other school districts across the nation, placed them under the control of education and business experts” (Lyons 2008, 11).

Without autonomy and paid abysmally—about $13,000 a year in today’s dollars, an amount frozen in place by law for 20 years—the teaching workforce of the city was powerless. Women elementary school teachers faced overcrowded classrooms, sexist pay schedules, and corrupt municipal political machines. During this time, “teachers were sometimes paid not in wages, but in ‘warrants’ promising future pay, which teachers had to cajole grocers and landlords to accept in lieu of cash” (Goldstein 2014, 68). Most teachers in the early 20th Century were single women, meaning they did not have husbands and fathers to fall back on in the same ways middle-class women could.

Precarity placed teachers among other working-class women, who do not have the freedom and access to power that bourgeois or middle-class women have. Former University of Chicago president William Rainey Harper canceled a paltry raise for teachers to drive women out of teaching. In response to protests, Rainey said “they should be happy they earned as much as his wife’s maid” (Goldstein 2014, 69). Susan B. Anthony—a teacher herself—articulated a more working class centered feminism at a time when middle-class women dominated the movement. Anthony said in a letter that when spreading the word about women’s rights meetings, she wanted “particular effort made to call out the teachers, seamstresses, and wage-earning women generally. It is for them, rather than for the wives and daughters of the rich, that I labor” (Goldstein 2014, 38).

Teachers’ politics lined up closely with those of industrial workers, and still do (Lampson 1919, 200-1) (Lyons 2008) (Thompson 2014). Unfortunately, reformers from upper class backgrounds were the ones who wielded the scythe of political power in America. Taylorist, “scientific management” schemes were at the heart of their ideological program (Goldstein 2014) (Lyons 2008). The goal was total control of the workforce. Political leaders routed working class children into vocational education. Corporations dodged taxes brazenly. Schools around the city fell into disrepair from chronic underfunding. After decades of tax evasion, and a corrupt patronage-based spending glut by CPS, the city and school system were nearly broke by 1929 (Lyons 2018, 12).

In this context, class struggle within the education industry escalated, first in Chicago, and then most areas east of the Mississippi (Martin 1999).

Class Struggle during the First Wave of Industrialization

By following the thread of the labor movement within education during this period—including how it was nearly crushed—we can understand another angle of education industrialization. Where there are workers, there is class struggle. Workers responded to industrialization by forming unions. Their surplus labor, stolen through the underfunding of schools and the inevitable longer and harder workdays that followed, allowed for private profit by lowering the cost of social reproduction (for the rich and powerful) to an absolute minimum. We will begin in 1916, when several localized teachers’ unions amalgamated into the American Federation of Teachers (AFT).

While the movement began entirely in cities with at least 30,000 people, it then spread like wildfire (Cook 1921). Teacher organization was now a national movement, sharply dividing the academic-managerial types of their day. Some university presidents and professors advocated reform to undercut the motivation for rebellion and prevent class conflict in a public-school system that served “all classes” (Cook 1921).

By 1920, the AFT counted 10,000 teachers in 180 locals, tripling its membership and more than doubling the number of locals (Martin 1999). But membership fell to under 5,000 in 1930. Above all, “strong opposition to teacher unionism by local school boards, school administrators, some teachers, and especially the business community” was the cause (Martin 1999, 200). Additionally, “yellow dog” contracts, the AFT “no strike” pledge, and low salaries hobbled organization (Martin 1999, 200-1). While the previous two decades brought victories for the CFT, with lawsuits to recover hidden corporate tax revenue and ensure equal opportunity for all within the schools (Martin 1999), the 1920s brought a withering defeat.

Attrition rates for AFT affiliated unions was high. Small, rural branches struggled to survive staff turnover and union busting. From 1920-21 alone, the number of operating locals dropped from 180 to 122 (Cook 1921). Even so, the AFT survived by clinging to urban strongholds.

Teachers' unions found solid footing in most major American cities by 1920, and as early as 1897 in Chicago. Founded by normally “docile” Chicago elementary school teachers like “Lady Labor Slugger” Margaret Haley, the CTF turned heads in 1902 when it affiliated not with the National Education Association (NEA), but the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) (Lyons 2008). Despite this militancy, professionalism as a construct encouraged many teachers to view themselves as middle-class public servants instead of workers.

The history of the NEA embodies this. For 100 years the NEA “portrayed itself as a professional organization little interested in bettering teachers’ wages or attaining collective bargaining rights” (Lyons 2008). Even so, they counted 200,000 members, increasingly schoolteachers, by the end of the 1920s (Cain 2009). In 1954 NEA membership topped 560,000 (Dewing 1969), consistently ahead of the AFT.

Ultimately, the NEA was not controlled by its rank and file, which overwhelmingly comprised women K-12 teachers. Instead, “school administrators, the largely male group...clearly maintained control of the association” through 1972 (Urban 2001). The NEA had a centralized organizational structure on the national and state levels, while the AFT functions with autonomous branches like the mainstream labor movement. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the NEA could be called a proper union after more than a decade of member upsurge drove administrators out.

Cornering the Market, 1880-1930

“Education entrepreneurs” prey on high poverty, colonized communities, as well as many poor white communities (Rooks 2017). In the early 20th Century, their common ancestors among the industrial magnates were men like John D. Rockefeller and Julius Rosenwald. They funded school construction for Black children across the South. It is no coincidence that this is during the same period that Jim Crow law and the white vigilantes with their nooses and red lines were forcing Black Americans into segregated zones. These philanthropists were not particularly active during Reconstruction, when Black Americans collectively struggled to construct public schools across the South and enshrine the right to public education in state constitutions. It’s only with the triumph of the Redeemers and destruction of the Populist Movement during the 1890s that these philanthropists’ consciousness spurred them to what constitutes “action” to rich people.

So, while white philanthropists who had “made their money in cotton, steel, railroads, minerals, and financial services” (Rooks 2017, 56) shaped the teaching workforce, they were also making their own captive customer bases out of Black families. Compulsory attendance laws aided their efforts. To these customers—mostly workers or sharecroppers—they “proposed educational curricula and forms offered only to Blacks and the poor” (Rooks 2017, 50). Rockefeller and Rosenwald “understood how…important an educated Black population was for the future economic prospects of businesses in that region, if not in the entire country” (Rooks 2017, 50). Their solution was to gather the cheapest labor power, buildings, and land, then combine it with the coercive power of the state to build a workforce prepared for brutal industrial capitalist workplace routines.

Southern legislatures—implementing their segregationist and terroristic agendas—used their power to divert dwindling federal money away from Black schools and teachers towards white ones. Northern white philanthropy remained the only real school funding source for Southern Black schools. The Julius Rosenwald Building Fund sent agents around the South to collect “all they thought they had” (Rooks 2017, 49) from Black communities. This money was meant for building schools and included a “match” from the foundation if a town raised enough starting capital. These rich whites now took advantage of Black students, teachers, and communities who had no other options besides underfunded, overcrowded schools. Black communities footed much of the bill and in exchange got some of the worst schools in the entire world as their benefactors raked in cash. Yet again, white Northern industrialists grew rich on capital they could then reinvest in their own companies, or into further business opportunities within education.

Following the Money

In the 1920s, corruption was rife, with Republican administrations in Chicago awarding “contracts for school construction and equipment to business groups that had direct links to city politicians” (Lyons 2008, 12). Here, we have another crossover between industries: education and construction. The Board of Education leased out land it owned in downtown Chicago to the The Chicago Tribune and other “business friends” for dirt cheap prices (Lyons 2008, 13). This history would rhyme in Washington, D.C. during the 1990s and early 2000s, when District politicians handed abandoned public school properties to emerging charter schools.

Chicago finances were similarly atrocious in the 1920s, so the Board kept the system afloat by going into ever deeper debt to banks through financial wizardry (Lyons 2008, 13). All of these examples reveal the pathways money followed as it circulated through the education system and generated profits for corporate and political elites.

Understanding the circular movement of commodities—goods placed on the market to sell for a profit—and how it generates capital is crucial. There are two types of commodity circulation: commodity-money-commodity (C-M-C) and money-commodity-money (M-C-M). Commodity-money-commodity is what normal people do. We sell a commodity—for us that is labor-power or something we made—in exchange for money, which we use to buy other commodities that we then use. Money-commodity-money on the other hand, means a person is holding onto the commodity until it is the right time to sell it to generate more money. A capitalist exchanges money for a house, not to live in, but to sell or rent for a higher value than what they acquired it for—to generate profit. Capital is the original value plus a change in value, which is added by exploited workers’ skill, creativity, and cooperation. Capitalists endlessly repeat this process, accumulating capital off the backs of billions of workers (Marx 1867).

Education itself has become a commodity that can be speculated and profited on, represented by the various degrees and certificates a person can use to enhance the value of their labor—if the gamble pays off. Student loan companies, universities, governments, and other stakeholders place bets on the potential futures of students. Will they finish high school? Drop out of college? Graduate but fall through the cracks into low-wage labor? Default on their loans? Work themselves to the bone to pay their loans? Become high-income workers who pay them back, no problem? Hit it big and create their own hotshot companies? No matter what, some rich person’s pocket gets lined. America is a casino, and the house always wins.

Equipment, workers, land, and buildings comprise the initial investment of money. Education workers refine the raw materials: the students, until they are ready to enter the job market. Everyone must then refine themselves to match up to the competition or fail and die. Women are doubly exploited. One set of people—mothers—perform reproductive labor for society. Their children were extracted as raw materials and working-class women teachers were then exploited to refine them.

Industries such as education, defense, and healthcare feature vast sums of public money flowing through them. This is great for private capitalists. Initial investment money comes from the public, and the product is simply handed over to the capitalist, for free. Lucrative building contracts, access to public land for cheap, and overlooked corporate tax evasion have a cost, one paid by education workers and students. Profit is unpaid wages. By reducing their expenses and soaking up public tax funds on the backs of teachers, the money returns to capitalists at a greater value. It absorbs new value from labor.

The only opposition corporate elites faced was from nascent teachers' unions like the Chicago Teachers Federation and “lady labor slugger” Margaret Haley, who were barred from striking by their own union leaders.

Then the Great Depression hit. To many, it appeared as if the resources for public education evaporated overnight. In response, the Citizens’ Committee on Public Expenditures (CCPE) formed in 1932, counting in its ranks the city’s “leading bankers, merchants, and industrialists” (Lyons 2008, 30-31). Their top priority was cutting education costs, so they usurped functions of city government relating to public schooling. Meanwhile, other public sector workers continued to receive job and salary protections—thanks to the spoils system of the city—and corporations had dodged tens of millions in taxes. The horrendous consequences immediately became clear as teachers went unpaid for months (Lyons 2008). Teachers paid for these cuts with their labor.

Conclusions

Ultimately, all these struggles illustrate the growing role class power had in shaping curriculum, staff discipline, and student population. The industrial ruling class of the country did not directly own the public school system. Counter-intuitively, the location of education in the public sector played a central role in its industrialization—not just in this first phase, but up through today—by allowing capitalists to bring the coercive power of the state directly to bear on workers, students, and their communities while placing the burden of cost on the public.

When analyzing the history of public education in America, it becomes obvious how public money consistently served private capital. This is clear in the union busting frenzy of the 1920s. It is also easy to see this in the way corporations used the state to rob the schools and harvest the next generations of workers in their wider system of speculation, profit, and plunder. Teachers at underfunded schools then had to work harder and longer for less pay. All the while, the professional middle-class remained complicit while crafting the architecture of our exploitation—assembling standardized tests, developing one-size-fits-all curriculum, and eroding job security through arbitrary evaluations. Our students, especially those from poor or colonized backgrounds, are siloed into schools where they and the staff have few, or no, other options through the power of the law. The isolation and atomizing of these communities enabled the capitalist class and their cronies in the government to generate capital from public education, reshaping it along the lines of industrial management and production.

The Industrialization of Education, Part Three: Schools in the United States, 1930-1975

Last time, we left off with the plunge into the Great Depression. Here, we examine the impact of the Depression and World War II on the industrialization of schools in the United States. Then, we analyze the expanding role of schools in social reproduction during the Post-War years.

Black, Derek. 2020. Schoolhouse Burning: Public Education and the Assault on American Democray. New York: PublicAffairs.

Bureau, US Census. 2022. “CPS Historical Time Series Tables on School Enrollment.” https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/school-enrollment/cps-historical-time-series.html.

Cain, Timothy Reese. 2009. “The NEA’s Early Conflict over Educational Freedom.” American Educational History Journal 36 (2): 361–75.

California Teachers Association. 2013. “Timeline of CTA History.” Politics and Advocacy. California Teachers Association. 2013. https://www.cta.org/about-us/history.

CLAIRE. 2020. “The Effect of Industrialisation on Education Policy and the School System.” Claire Garside (blog). January 22, 2020. https://clairegarside.com/2020/01/22/the-effect-of-industrialisation-on-education-policy-and-the-school-system/.

Cook, William. 1921. “Rise and Significance of the American Federation of Teachers.” The Elementary School Journal 21 (6): 444–60.

Dewing, R. 1969. “The National Education Association and Desegregation.” Phylon 30 (2): 109–24.

Dewing, R. 1973. “The American Federation of Teachers and Desegregation.” The Journal of Negro Education 42 (1): 79–92.

Duncan, Mike. n.d. “The Second French Empire.” Revolutions Podcast. https://thehistoryofrome.typepad.com/revolutions_podcast/2018/05/81-the-second-french-empire.html.

Farm, Brotato. 2022. “Thoughts on Sleepy Hollow.” Criticism and short fiction. Forest of Doors (blog). May 30, 2022.

https://comradebroguy.substack.com/p/thoughts-on-sleepy-hollow/comments.

Foner, Philip. 1970. “The IWW and the Black Worker.” The Journal of Negro History 55 (1): 45–64.

Gershon, Livia. 2017. “The 19th-Century Activist Who Tried to Transform Teaching.” JSTOR Daily. August 7, 2017. https://daily.jstor.org/the-19th-century-activist-who-tried-to-transform-teaching/.

Goldstein, Dana. 2014. The Teacher Wars: The History of America’s Most Embattled Profession. First Edition. New York: Anchor Books.

Grimké, Charlotte Forten. 2011a. “Life on the Sea Islands (Part I).” The Atlantic, November 9, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1864/05/life-on-the-sea-islands/308758/.

———. 2011b. “Life on the Sea Islands (Part II).” The Atlantic, November 9, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1864/06/life-on-the-sea-islands-continued/308759/.

Gross, Robert. 2018. Public Vs. Private: The Early History of School Choice in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Haley, Margaret. 1904. “Why Teachers Should Organize.” Journal of Education 60 (13): 215–16, 222.

Hillary, Brady, and Franky Abbott. 2015. “A History of US Public Libraries.” Digital Public Library of America, September. https://dp.la/exhibitions/history-us-public-libraries.

Hlavacik, Mark. 2012. “The Democratic Origins of Teachers’ Union Rhetoric: Margaret Haley’s Speech at the 1904 NEA Convention.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 15 (3): 499–524.

Lampson, L. V. 1919. “American Federation of Teachers.” The Journal of Education 90 (8): 200–201.

Lyons, John. 2008. Teachers and Reform: Chicago Public Education, 1929-1970. The Working Class in American History. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Mader, Jackie. 2012. “The Rise of Teacher Unions: A Look at Union Impact over the Years | HechingerEd Blog.” Educational. HechingerEd (blog). September 19, 2012. http://hechingered.org/content/the-rise-of-teacher-unions-a-look-at-union-impact-over-the-years_5601/.

Martin, Don. 2001. “Origins of the American Federation of Teachers: Issues and Trends Between the Two Great World Wars.” American Educational History Journal 28.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. 1867. “Capital, Volume One.” In The Marx Engels Reader, edited by Robert Tucker, Second.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2008. “Table 32. Historical Summary of Public Elementary and Secondary School Statistics: Selected Years, 1869–70 through 2005–06.” U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d08/tables/dt08_032.asp.

Rooks, Noliwe. 2020. Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education.

https://bookshop.org/p/books/cutting-school-the-segrenomics-of-american-education-noliwe-rooks/7402780?ean=9781620975985&next=t.

Shelton, Jon. 2017. Teacher Strike! Public Education and the Making of a New American Political Order. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Taylor, Clarence. 2011. Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union. New York City: Columbia University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/tayl15268.5.

Thompson, John. 2014. “Teachers Are Workers.” News and opinion. Huffpost (blog). January 2014. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/teachers-are-workers_b_4536290.

Urban, Wayne. 2001. “Courting the Woman Teacher: The National Education Association, 1917-1970.” History of Education Quarterly 41 (2): 139–66.

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, radical pedagogy, and art.

Support Our Work

All our public work is freely available with no paywalls, and always will be. But if you want to help our collective cover the costs of hosting webpages, creating agitprop, and finding research materials, then please consider signing up for a paid subscription or donate to us on Ko-fi if you don’t want to give money to substack. With enough support, we can begin sharing the funds among collective members for them to use on various projects and pay others for any work they do for us—such as translating or printing materials.

Fascinating! As you mention, "history would rhyme in Washington, D.C. during the 1990s and early 2000s, when District politicians handed abandoned public school properties to emerging charter schools." Everyone should read this before "learning" about the supposed wonders of for-profit EduTech and charter companies.