Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part 10: Industrial(?)

Revolutionary unions should strongly consider adopting an industrial organizing model that can effectively coordinate the takeover of production during a revolutionary upheaval.

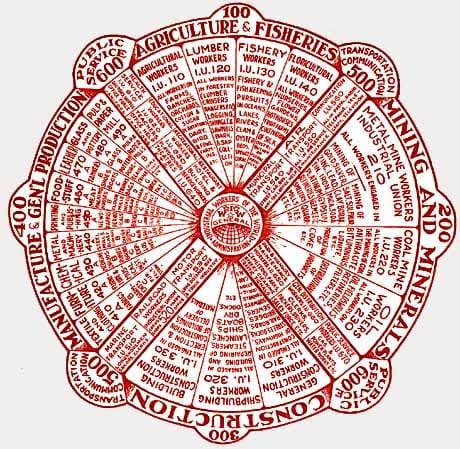

This section of "Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement" has been met with skepticism and criticism by some who argue that industrial union strategy is not necessary to be a revolutionary union. One fellow worker argued that requiring revolutionary unions to adopt an industrial organizing model could cut off possibilities for alternative forms of solidarity and organization between workers. For example, a union organizing model that incorporated all public service workers—such as teachers, bus drivers, postal workers, hospital workers, and sanitation workers—might be overlooked when organizing strictly by industry. Advocates of industrial unionism could point to the IWW’s groupings of closely related industries into departments, including Department 600 for public service workers, as a solution. Some fellow workers compared industrial organizing to sectoral bargaining—which is not necessarily revolutionary. Other fellow workers disagree with the comparison entirely. It is also possible that the necessity for a revolutionary union to organize industrially is confined geographically to North America, or even just the US.

We hope that you will help us resolve this debate by joining the discussion. Please leave a comment, or post in our chat if you’re a subscriber.

Business unions have all demonstrated their insufficiency in achieving or maintaining even modest social democratic goals such as universal healthcare. That’s because they lack any coherent strategy outside of winning contracts and electing Democrats (unless you’re even more of a clown, like Sean O’Brien). Besides their class collaborationist nature, this lack of strategy can be explained by their organizing strategies. The main choices for business unions consist of: craft unionism, general unionism, and a hybrid of the previous two. Revolutionary unions organize industrially.

For a full, yet concise, explanation of what industrial unionism is, please see Justus Ebert’s 1919 pamphlet “The Most Important Question.” Over 100 years later, it still holds up, and is currently being adapted for modern use by the IWW. A short definition is that industrial unionism is an organizing model that unites workers by the type of industry they work in, rather than their specific job role. Generally, industries are distinguished by the products or services they generate, or how those goods are distributed throughout society. According to this thinking, all workers in the same workplace should be in the same union local, regardless of occupation, education level, or any other ultimately arbitrary division. Further, all workers in similar workplaces across the same geographic area should be included, too.

Industrial unionism carries the potential to go on a class offensive against capital itself. A core principle of this organizing philosophy is that all industries are fundamentally tied together in the whole of social production and reproduction. The logical conclusion is that our solidarity with all other workers is the key to our victory, while disunity is the mechanism of our defeat. Look at our shared working class history of the last few hundred years. It is a history filled with betrayal, prejudice, and abuse: men betraying women during the Witch Hunts, white supremacy and Western imperialism, violence directed against one another and our communities. Ebert describes industrial unionism as “a method of social reconstruction. It is a means by which the basic activities of society may be continued when capitalism shall have been overthrown by its own failures and class conflicts.”

Industry-wide strategy is a necessity for proletarian victory on the terrain of production. Existing labor law attempts to confine working class resistance to specific workplaces as much as possible. Capital, meanwhile, has no restraints; especially under Neoliberalism. Not even international borders can stop the flow of trillions of dollars of capital, all of which is simply stolen labor.

Industrial unionism contributes to the prefiguration of a future democratized economy. It doesn’t matter if we’ve organized the whole economy when a situation of dual power emerges, what matters is that we already know how to horizontally organize our workplaces. We can then work to extend these new societal relations to everyone through persuasion and education. Those of us who work in education will have a special role to play in this process. Only through organizing industrially can the workers create a truly independent pole of power during a revolutionary transition, and by doing so prefigure a wider transformation in social relations that resolves the tension between worker’s control and wider societal needs.

Accomplishing this requires honing in on strategic industries first. That does not mean abandoning small or marginal workplaces, of course. Most of the business unions turn down requests for external organizing support from small workplaces because it’s not “worth it” for them from an economic perspective. We don’t want to emulate that. On top of that, at every stage of capitalism, including this one, smaller firms make up the majority of economic activity. That said, large workplaces and employers represent important objectives for a revolutionary workers’ movement to conquer. Taking the example of education, school districts in the US are usually some of the biggest employers in a city, county, or even state. Hospital facilities, too. And that’s not to speak of the massive warehouses and logistics networks spanning the world. Revolutionary unions must target their organizing by industry, embedding salts and gathering recruits in as many of the different types of workplaces in the industry as possible. If possible, this organization should be spread internationally.

That's all for part ten! Check back next week for part 11, we’ll delve into the necessity of revolutionary unions rooting themselves in other social movements, as well as their own communities.

Work in education? Get involved!

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get in front of an audience, get in touch! Check our post history to get a sense of what we are looking for, but we are open minded to all sorts of submissions.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

Support Our Work

All our public work is freely available with no paywalls, and always will be. But if you want to help our collective cover the costs of hosting webpages, creating agitprop, and finding research materials, then please consider signing up for a paid subscription or donate to us on Ko-fi if you don’t want to give money to substack. With enough support, we can begin sharing the funds among collective members for them to use on various projects and pay others for any work they do for us—such as translating or printing materials.