Ordering the Arena of Modern Life: The Role of World's Fairs in the Education Industry

This essay makes the case for the IWW and other revolutionary unions to strategically target world's fairs and other expositions for organizing.

Introduction

The hierarchical, authoritarian social relations of our modern world emanate from the imaginations of the capitalist ruling class, who then project their visions onto the rest of humanity through the state and capital. From the earliest days of capitalism, education has been one of the main means of making ruling-class visions for their subject populations a reality. However, the construction of the capitalist education industry has unleashed a mass of pedagogical machinery that the ruling class struggles to control. The arena of modern, capitalist education serves to compose and impose capitalist social hierarchies. But it also opens up spaces for resistance by workers and their communities.

World's Fairs, also known as universal or international expositions, have occupied the commanding heights of the education industry for nearly 200 years, helping members of the ruling class maintain their control over society. Institutionally, the purpose of these expositions is to set the ideological agenda that workers in museums, schools, and libraries transmit to the wider public. They also function as a venue for bosses and politicians to coordinate in informal, fluid ways that transcend more formal, often inflexible, capitalist power structures. Many have wondered how capitalism has weathered so many of its self-created crises like the Great Depression and avoided defeat by the proletariat. Studying the historical impact of world’s fairs explains a significant part of why.

But what are world fairs? They are international exhibitions of industrial, scientific, technological, and artistic achievements of nations and corporations. Robert Rydell—a professor emeritus of U.S. cultural history at Montana State University—describes them as a “veritable web" that "ringed the globe, giving form and substance to the modern world"1. While we can't delve into a detailed history of the world's fairs, what we will address is:

why World's Fairs should be considered part of the education industry;

the ways the employing class uses World's Fairs to maintain and spread their hegemony;

what next steps the international working class, especially those already in revolutionary unions like the IWW, should take to organize at these expositions;

and a brief sketch of the role world's fairs and education more broadly can play in the revolutionary transition out of capitalism.

We hope that IWW organizers will use this essay to take the first steps towards organizing at universal expositions.

World’s Fairs as Educational Institutions

But don't events like expositions and world’s fairs have more to do with entertainment than education? Why should an industrially organized international union of education and research workers (IU 620)2 affiliated with the IWW be the ones to shoulder the primary responsibility for initiating confrontations with the employing class at these international expositions?

Because world fairs sit at the pinnacle of the education industry, which plays a central role in the accumulation of human capital. Human capital is the built-up knowledge and skills that make a workforce productive. The production and circulation of human capital manufactures a person who has been inculcated with the knowledge, ideology, discipline, and culture that primes them to serve the whims of business owners and politicians. Education is also part of the invisible clockwork machinery that sets the "unstoppable momentum"3 of capitalist life in motion. Education also serves as a connecting point—a node—between different industries and social groups with varying levels of power. The education industry includes:

public, charter, and private pre-Kindergarten through 12th grade schools;

post-secondary institutions like colleges, universities, and trade schools;

libraries and archives, including public library systems, academic libraries at universities and colleges, school libraries in K-12 schools, and special libraries like presidential library museums;

the Exhibitionary Complex of cultural institutions like museums, expositions, and heritage sites;

non-profits, foundations, and government departments geared towards education research, funding, and curriculum development;

corporate and government job training and lifelong learning facilities;

the amorphous armies of gig tutors and tutoring companies that surround the entire industry;

and educational technology (edtech) firms.

To understand the connections between world’s fairs and education, we must trace our modern education system back into the mists of the past. When we do, it becomes clear that fairs and the courtly societies of nobles in Europe during the Early Modern period are some of its earliest evolutions. Alongside the early universities that trained the future clergy and statesmen, fairs and court societies were institutions that, despite appearing as opposites, combined to project elite ideas onto the rest of society. While the courts of the nobility were seemingly isolated from the populations they governed, they contained the embryos of modern libraries and museums. Back then, these private literary collections and cabinets of curiosity were the playthings of the rich and powerful and were their exclusive domains.4

However, the emergence of capitalism—the endless lust to accumulate as much capital as possible—meant that the nobility, clergy, and rising bourgeoisie had opened a Pandora's box. One that unleashed titanic economic, social, and political forces they could not fully control. They needed ways to regulate these forces that were always threatening to tear society apart. Controlling sources of information and knowledge production is usually more sustainable than trying to suppress them outright. By harnessing the popular appeal and mass scale of the fair, they were able to spread their ideologies outside the small worlds of their courts to ever-increasing numbers of ordinary people. Especially to those in the rising middle classes. Even though international expositions feature plenty of entertainment, their overall function is educational.

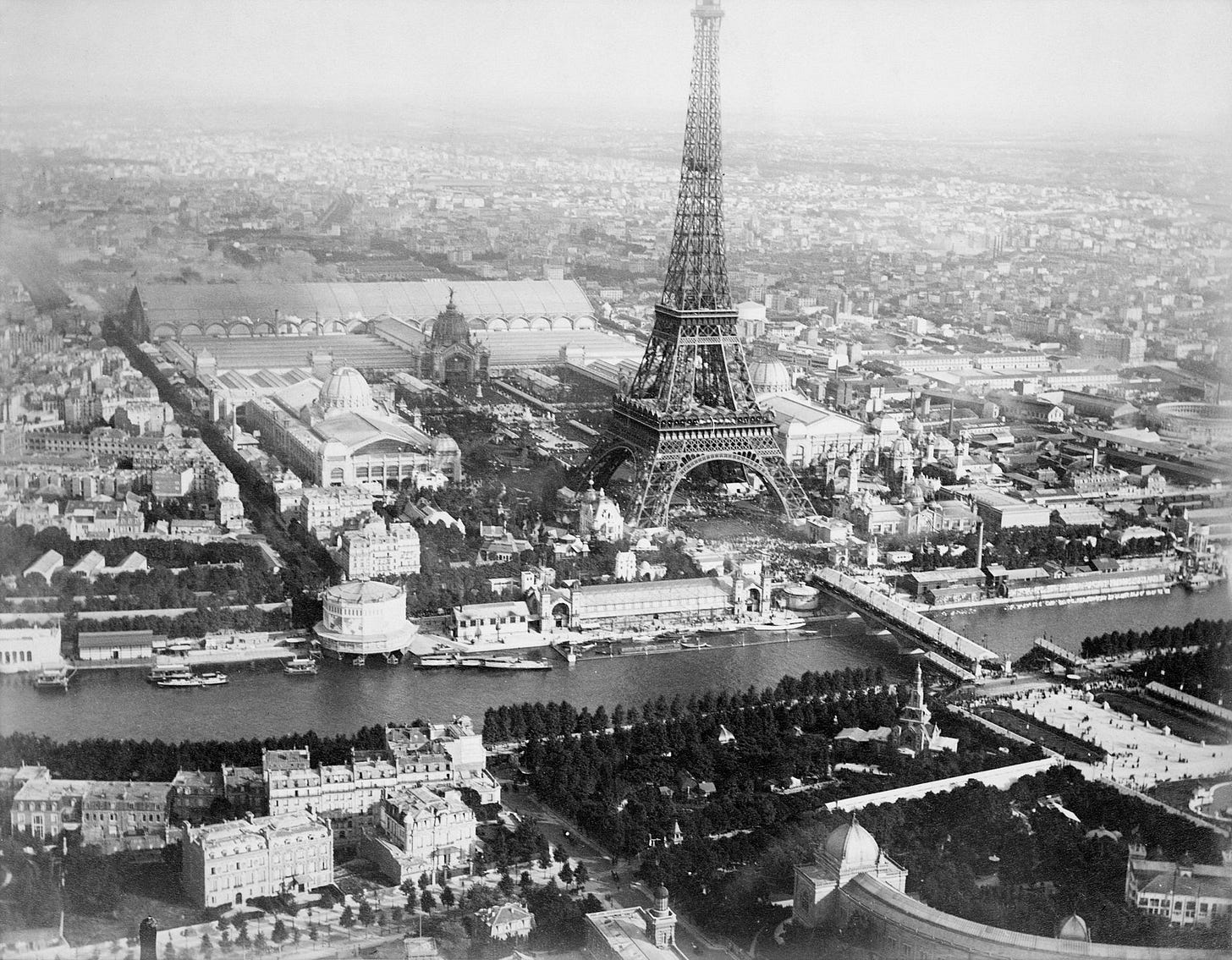

By the 19th Century, their disparate efforts had coalesced into the museum and the world's fair. The United Kingdom hosted the first world’s fair in 1851, called The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. After that, a discernible world’s fair movement replicated and spread these expositions across Europe, the United States, Australia, and now Asia.

Looking at some examples of connections between World's Fairs and other more recognizably educational institutions makes their pedagogical purpose clearer. As these temporary events recede into memory, they consistently leave behind permanent educational institutions in and around their host locations. For example, world’s fairs are a significant producer of museums. The famous 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition “inspired leaders from Buffalo to Saint Louis to San Diego to combine palatial architecture, a park location and the occasion of a world’s fair to establish museums”5. Even when not directly spawned by a world's fairs, museums end up housing countless objects from them. An "incessant and multifaceted set of exchanges" between world's fairs and museums form what scholar of museum studies Tony Bennett referred to as an "exhibitionary complex"6. This complex is essential for recycling artifacts into the production of human capital. It was the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, for example, that allowed for the first major expansion of the Smithsonian Institution beyond its original castle building. Today, it is the largest museum system in the world.

Simultaneously, "techniques of crowd control" developed during international expositions "influenced the design and layout" of amusement parks and museums.7 Amusement parks and museums then formulated even more new methods of crowd control and social regulation. Methods that the world’s fair could transmit to the public. Museums, meanwhile, specialize in manufacturing classification systems that expositions weave into every aspect of modern life. World’s fairs, then, are an educational node that allows the techniques of social control of the rich and powerful to migrate freely between their normally rigid corporate and governmental institutions.

Beyond museums, universities are almost always involved in fair planning and execution, with individual faculty members or whole departments participating in some way. All of the American fairs through the end of World War I "included ethnological villages sanctioned by prominent anthropologists" who organized summer class sessions around them.8 Most notably, the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Names of university presidents and high-ranking academics pop up repeatedly in lists of fair managers, planning commissions, and consultants. School teachers received free, guided tours around American world's fairs sites to impart ideas that would influence their teaching methods. They were also a common destination for school field trips. American expositions helped set the agenda in its nation's K-12 schools. Which then disseminated narratives and rituals throughout the population—like the pledge of allegiance, the reverence for Christopher Columbus, and the obsession with cars—that are still dominant to the present day.

The NAMM Show reveals a direct connection between performing arts education and the Exhibitionary Complex. Hosted by the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM), it is a different type of exposition altogether. Originally just the organization’s annual convention and a trade show, it was renamed to the NAMM International Music & Sound Exposition from 1976 to 2002. By the 1970s, NAMM had evolved beyond a national retail association—now, it had members from all over the world, including companies involved in instrument production and distribution. Even though it no longer calls its annual gathering an exposition, it still retains all the characteristics of one.

Not only does it organize itself around exhibits featuring music companies from around the globe, the NAMM Show goes out of its way to invite music educators. The College Music Society (CMS), for example, offered over two dozen “educational and networking sessions for college music students and faculty” at the 2023 NAMM Show. There were more than 50 classes for K-12 music teachers and students. Ideologically, the NAMM Show emphasizes their role in creating the future of music and sound, especially for the “global music products, pro audio, and entertainment technology industry”. Capital generated at each NAMM Show then gets reinvested into music education programs through grants meant to continually increase exposition profits. According to ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer, most of NAMM’s income derives from program services and investments. Before the pandemic, NAMM reliably had a net income of one to two million, with millions a year spent on executive compensation.

Together, these mutual connections between world’s fairs and every other major sector of the education industry prove that they should be included as part of education (IU 620) in the IWW's system of industrial classification.

The Capitalist Use of Pedagogical Machinery

Because of their temporary, transient nature in the short term, world’s fairs are extremely durable, yet versatile, in the long term. That makes them a perfect arena for the elite to assert their legitimacy and competence by refuting (or ignoring) criticisms, while directing public attention towards a spectacle of a better future. From their beginnings, universal expositions were elite reactions to social crises and upheaval. The 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations occurred in the wake of the 1848 Revolutions in Europe. Amid mass worker strikes and riots after the Panic of 1873, American elites responded with the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. And the Great Depression sparked a flourishing of world's fairs. Rydell argues that "American exposition promoters, usually industrialists and local civic leaders acting with federal government sponsorship" emphasized "the marriage of science and technology to the modern corporation as the blueprint for building a better tomorrow"9 during these Depression-Era fairs. President FDR actively promoted world fairs and funneled considerable support from New Deal programs towards expositions hosted in the United States.

International expositions are powerful apparatuses of pedagogical machinery that can build a firewall against the working-class revolution. For example, after World War I, European governments "revitalized" world's fairs specifically geared towards "promoting national imperial policies"10. Of fifteen fairs hosted in the United States between the world wars, "roughly half were explicitly devoted to the preservation and extension of empire"11. Some of France's most important fairs were planned by individuals who were "possessed of the conviction that the lessons of colonial administration could be applied to ordering the French body politic”12.

These colorful, ephemeral arenas are also an ideal space for influential business people and politicians to build relationships and coordinate across formal institutional borders. First, there is the jockeying against other nations to receive the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE)'s official approval to host a world’s fair. Fairs are often, but not always, partially supported financially by their respective host nation's government. This means a lot of lobbying from business interests for local, state, and national government investment in fairs.

Civic associations and the wider public also help raise funds, gather items to exhibit, and document their participation in the fair. By leaning on the public to aid with "generating exhibits for the fair" they "facilitated popular identification with and acceptance of the directions being given to American culture...by nationally prominent elites"13. While a universal exposition hasn't been hosted in the United States in decades, they are still important internationally. China’s Expo 2010 in Shanghai, for instance, was attended by over 70 million people—the most in the entire history of world’s fairs. And they serve the same purposes today as they always have for the ruling class, as "proven means for lending legitimacy to their positions of authority"14.

NAMM’s exposition is one of the nodes that links the education industry to the Non-Profit Industrial Complex (NPIC). The NPIC “serves to reinforce the status quo and discipline efforts to disrupt it”15. While NAMM’s role in funding educational programs through grants seems altruistic on the surface, it conceals the same basic authoritarian social relations embodied by capital. Claire Dunning, an assistant professor at University of Maryland, argues that the power of grants to fund causes and organizations “is also the power to withhold and extract”16. Grants erect hierarchies between funders and recipients, which facilitates “surveillance, evaluation, and control of the recipient”17. And by “decentralizing the delivery of services, they simultaneously expand the state’s reach and operations, while also making such influence more difficult to see”18. Dunning specifically analyzes how grantmaking integrates non-profits into a framework controlled by the state, but acknowledges that the same is true of money granted by private actors like foundations. Further inquiry is needed to understand the ways NAMM specifically wields this power within the education industry. But there is no doubt that it will reveal more about the pedagogical machinery composing expositions, and the role these events play in emanating the pretensions of the elite to the population.

Organizing the Fairs

To defeat capitalism, the international working class must conquer the means of production and transform them to construct a communist society. That means taking the fight to the ruling class on every front possible. World’s fairs and other expositions are effectively one of the major nuclei of capitalist ideology and planning. Worker-militants should organize in, around, and against them. First, worker-organizers should research the most recent world fairs—hosted by the United Arab Emirates, Kazakhstan, Italy, and China—and generate reports about the working conditions, any controversies surrounding the fair, and collective attempts to address them. Next, we must identify when and where the next universal expositions are being held: Osaka, Japan in 2025; Belgrade, Serbia in 2027; and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in 2030.

From there, we must take stock of our capacity as a revolutionary union movement, and the IWW specifically, to organize around any of these upcoming world fairs. The Osaka exposition opens in April of this year (2025). But there is no meaningful IWW presence or known contacts in any local revolutionary unions. Expo 2027 Belgrade, in contrast, is a more viable target. While the IWW does not yet have a meaningful presence in Serbia, its overall regional administration covering most of Europe could still take many immediate actions regarding Expo 2027. These could include:

researching the hiring patterns of the fair (where are workers being hired from? what are their socioeconomic backgrounds? who is in charge of hiring and firing?);

identifying funding sources;

and keeping tabs on exposition planning, construction, and promotion.

Fellow workers in Europe could designate a single person, at first, to get the work started. If there are already individuals or committees doing corporate research in the European administration, this might be a worthwhile project for them. Then, with some information on who the workers are and where they might be, an IWW delegate could gather worker contacts and encourage workers hired for expositions to collectively organize. IWW organizers could also get jobs related to the exposition and act as salts to spur collective action.

If successful, worker-organizers could spread the struggle, using the tight timetables of fair preparation and the public visibility of the expositions themselves to their advantage. During the fairs themselves, workers and their supporters can take some cues from the past. French anti-imperialists organized a "counter exposition" to the 1931 International Colonial Exposition. Black Americans consistently protested segregationist policies at world’s fairs in the U.S., and sometimes organized counter-expositions. Organizations and individuals have come together to fight for fairs that include equally and represent accurately all types of people. And of course, there are cases of fair workers taking collective action, though there is scant documentation of their struggles. A revolutionary union could stage protests and counter expositions designed specifically to spread militant organization among the workers building, then running, the expositions.

This organization would not last, because expositions themselves only exist for a short, fixed period of time. But its effects would ripple across the world right alongside the political, economic, and cultural effects of the fair itself. Displayed beside all the wonders of the fair would be the international working class, united in direct action for all to behold. And this is where an industrially organized union for education workers affiliated with the IWW could intervene.

Solidarity unionism—the IWW's most developed organizing model—is well-suited for organizing workers connected to international expositions. As an approach, it de-emphasizes the importance of signing formal collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) and pursuing legal remedies for union busting. An immense swathe of the United States economy falls outside the purview of the NLRB. At these workplaces, “pure” solidarity unionism is, in fact, the best approach, and one that no other union in the U.S. can replicate. And even if universal expositions never come back to the U.S., many of the countries that host them in the 21st Century have even worse labor laws. Without effective legal mechanisms to enforce protections for exposition workers, militant workplace organizing committees supported by a union like the IWW are their best bet at fighting back.

The IWW would also gain. Besides the public visibility for a future Industrial Union 620, worker-militants activated by the IWW would scatter into all sorts of industries and places around the continent. These workers would carry the revolutionary class struggle wherever they go. In Serbia, the IWW would likely gain a reputation as a fighting union with a strong base among its working people. Organizing workers at international expositions would also present excellent opportunities for the IWW to practice long-term goal setting, planning, and logistical coordination.

Experience from organizing at more ephemeral world’s fairs could be translated into organizing at more permanent exposition and entertainment workplaces. At the NAMM Show, militant direct action could help spread the union struggle to music educators—who are frequently isolated from other education workers. That leaves them more vulnerable to ideological programming that is harmful for students by cult-like organizations such as Drum Corps International (DCI) and Bands of America (BOA). NAMM hosts its exposition at the same location every year: Anaheim, California. Future IWW Industrial Union Branches (IUBs) of education workers in Southern California could take the lead in targeting it. Hopefully, the prospect of organizing at expositions itself helps motivate education workers in the IWW to formally charter an Industrial Union administration (IU).

Another advantage of organizing at world’s fairs is that they are gateways to organizing in the entertainment industry. Strategy and tactics pioneered at universal expositions could be applied at a diverse range of entertainment industry workplaces from amusement parks to theme parks to movie sets to arcades. EPCOT park at Disney World Resort is frequently described as a permanent world’s fair. It even functions like a universal exposition by conjuring visions of humanity’s glorious, scientific future—like the WorldKey system that might have helped inspire the Internet. A future Industrial Union for Performing Arts, Recreation, and Tourism Workers (IU 630) and IU 620 could collaborate to target workplaces like EPCOT.

It's much harder to sketch out any strategy or tactics for Expo 2030 Riyadh. But five years is bound to present opportunities as the IWW and other revolutionary unions grow in size and strength. Our industrial model would be a potent tool for organizing supply chains across borders, too. Expo 2030 Riyadh could be a means of spreading revolutionary labor organizing among migrant workers who will constitute most of the workforce. Many millions of migrant workers are caught up in global supply chains and logistics networks. And it's well-known that countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Italy, and Serbia exploit these vulnerable workers. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are particularly notorious for their de facto enslavement of migrant workers. Expo 2020 in Dubai was plagued with accusations of abuse towards migrant workers. Universal expositions, then, are a portal across borders, ethnicities, religions, and all other dividing lines within the global proletariat.

Communist World’s Fairs?

Finally, an international, industrially organized, union body for education workers could harness world’s fairs after a successful revolutionary upsurge to spread the revolution, build revolutionary culture, and coordinate the construction of a communist society. It's unlikely that a worker's revolution would immediately succeed around the entire world. We'll need to bring the organs of revolutionary worker power together in directly democratic forms to build a new world in the burning shell of the old one.

Historically, a primary cause of our failure to set off a truly international revolution is because of various political divisions within our class. Sectarian divisions of all kinds between countless factions of workers have undermined every proletarian revolution in modern history. By trying to impose our differing visions of what the revolutionary transition out of capitalism should look like on each other, we fracture the unity needed to create a new system. That lays the groundwork for the reimposition of capitalism. Socialist world’s fairs could become a key institution for bringing differing revolutionary movements from all over the globe together to cooperate horizontally.

Revolutionary world fairs would facilitate working class unity across borders, cultures, ethnicities, political stances, and all other dividing lines within the proletariat. The structure of international expositions would provide a platform for discussion, persuasion, and coordination without coercion. Political jockeying for influence—unlikely to be abolished until long after the revolution begins—will be directed away from violent conflict and into the spectacle of the fair. Disagreement and intense argumentation wouldn't disappear, but revolutionary world fairs might serve as a venue that produces coexistence. A place where our differences could be expressed openly and peacefully. They'd allow for the various revolutionary zones to begin building international governmental institutions that could defend and spread the revolution. Of course, they'd accomplish this in tandem with a variety of internationalist revolutionary institutions. But at the expositions, revolutionary zones could show off their accomplishments, allowing everyone to learn about and copy each other's best ideas and innovations.

In the hands of industrially organized education workers, the pedagogical machinery that universal expositions represent would be a powerful institution for building a revolutionary, international society with the working class in power.

If you subscribe to our newsletter, please take a moment to complete our 2025 Reader Survey:

Rydell, Robert. 1993. World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://archive.org/details/worldoffairscent0000ryde

For explanations of industrial organizing and its advantages in the modern IWW, please see Justus Ebert’s “The Most Important Question” and the Addendum to Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, respectively.

Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Addendum: A Revolutionary Vehicle? The Role of the IWW

The IWW, at its strongest, represented a fusion between the political and the economic, transcending the artificial and arbitrary divide between the two. By taking positions on specific political issues—expressed through direct action—as a union, we build organized nuclei for the proletariat to use, while pointing them in a revolutionary direction.

Bennett, Tony. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Culture : Policies and Politics. London; New York; Routledge. Page 4. The Birth of the Museum (pdf version)

Battles, Matthew. 2003. Library: An Unquiet History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-02029-0.

Schwarzer, Marjorie. 2006. Riches, Rivals, & Radicals: 100 Years of Museums in America. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Museums. ISBN-10: 1-933253-05-3. https://archive.org/details/richesrivalsradi0000marj

Bennett, Tony. 1995.

Ibid. Page 5.

Rydell, Robert. 1993. World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Page 21. https://archive.org/details/worldoffairscent0000ryde

Ibid. Page 7.

Ibid. Page 61.

Ibid. Page 61.

Ibid. Page 61.

Ibid. Page 29.

Ibid. Page 6.

Dunning, Claire. May 5, 2023. “The Origins of the Nonprofit Industrial Complex”. New Haven: Law and Political Economy Project. https://lpeproject.org/blog/the-origins-of-the-nonprofit-industrial-complex/.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Suggestions for Further Reading and Viewing:

Boisseau, TJ; Markwyn, Abigail. 2010. Gendering the Fair: Histories of Women and Gender at World’s Fairs. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07749-4. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780252077494

Elias, Norbert. 1983. The Court Society. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-71604-3. https://archive.org/details/courtsociety00elia

Rydell, Robert. 1984. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73239-8. https://archive.org/details/allworldsfair00ryde.

Rydell, Robert; Findling, John; Pelle, Kimberly. 2000. Fair America: Worlds’ Fairs in the United States. Washington, D.C. and New York: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 1-56098-3841-1.

Education History Video Playlist

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Work in education? Get involved!

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get in front of an audience, get in touch! Check our post history to get a sense of what we are looking for, but we are open minded to all sorts of submissions.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

If you don’t have the capacity to get involved, we encourage you to share our work with other educators—especially your coworkers. For our readers who don’t work in education, please send our creations to any education workers you know.

Support Our Work

All our public work is freely available with no paywalls, and always will be. But if you want to help our collective cover the costs of hosting webpages, creating agitprop, and finding research materials, then please consider signing up for a paid subscription or donate to us on Ko-fi if you don’t want to give money to substack. With enough support, we can begin sharing the funds among collective members for them to use on various projects and pay others for any work they do for us—such as translating or printing materials.

Wow, what a fascinating dive into the hidden power of World’s Fairs. I loved how you unpacked their role as educational tools for capitalist control.

It reminded me of an article i read about a forest area in brazil being cut down and a road built in its place since cars needed to pass to go to an excluded area for a climate change event.

I also believe that, as socialists, we could do better online in terms of setting the agenda. I would love to have a conversation with you about this if you are interested. I just inboxed you.