Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part 11: Rooted in Communities and Social Movements

We cannot let the state and capital drive a wedge between workers and their own communities. Revolutionary unions must forge alliances with community groups and root themselves in social movements.

This is the eleventh part of an essay series on revolutionary unionism. If you have not read the previous entries, you can start at part one here:

Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part One: Introduction

The working class today stands at a crossroads amid deepening, interlocking crises. With education workers leading the way, the labor movement is in the early stages of revitalization—the awakening of a sleeping giant. For all their admirable successes, though, the prominent trade unions themselves have historically played a key role in constructing div…

Throughout the 20th Century, the employing class and the state were able to exploit divides between labor unions and other social movements to defeat both. Revolutionary unionism seeks to repair these deep wounds and to root itself among our communities and social movements outside the workplace. Joe Burns provides an excellent way of understanding the importance of rooting ourselves like this: “Whereas class struggle unionists see themselves as fighting for all members of the working class, business unionists narrowly represent their members even when they are at odds with the broader working-class interests.”1

Bargaining for the Common Good represented a fundamental step forward for our movement when first developed by teacher unionists in the CTU. Teachers’ unions have long linked their workplace struggles with the wider working class struggles for housing, racial justice, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ liberation, and more.2 Just because these movements are often not explicitly radical or revolutionary does not mean our unions should distance ourselves from them. Quite the opposite. It is our responsibility as revolutionary workers to agitate, educate, and organize the entire working class. That means providing an example that can demonstrate the necessity of revolution, as well as the integrity of our organizations. Otherwise, community social justice movements and revolutionary labor unions will advance separately into our respective pitfalls. We need an ecosystem of organization.

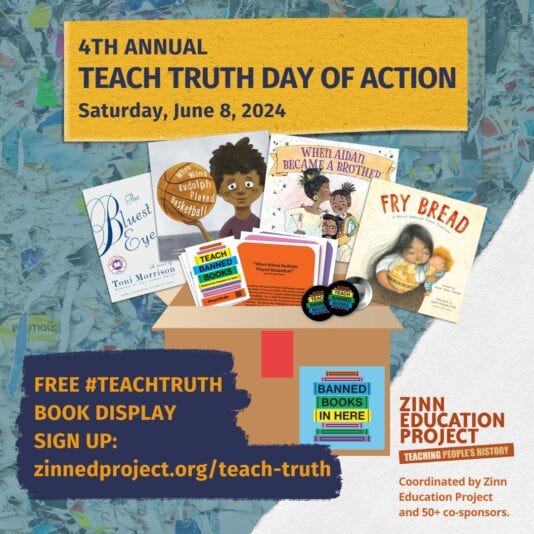

Take, for example, the education workers involved in groups like Teaching for Change and Rethinking Schools. In the wake of attacks on teaching the truth and book bans, these groups organized an ongoing movement they call the “Pledge to Teach the Truth.” This pledge has created an undercurrent of resistance across much of the US, with school, library, and museum workers formally and publicly pledging to break any laws restricting their autonomy to teach the truth about slavery, patriarchy, war, the genocide in Palestine, and more. Many, of course, are already doing so without even being aware of the campaign. Such bravery is admirable in the face of rabid fascist groups such as Moms for Liberty. We as revolutionary unionists can learn from this spirit, cultivate it, and spread it across the whole class independent of politicians and the NPIC. Otherwise, we risk falling behind the business and labor liberal unions, who have largely embraced social justice causes.

By cooperating with social justice movements and rooting ourselves in our local communities, we build an organizational firewall against becoming an isolated fragment like most communist and anarchist groups. In an interview with the Working Class History project, LRBW organizer General Baker emphasized that the group had “at least three community organizations that we were solidly based in while we organized in the plants”. He explained this in the context of how essential the role women outside the workplaces played in the League was. With connections in the community, the LRBW mobilized autonomously organized students to help new plant-based collectives distribute their newspapers. Preachers stood outside the plant gates and delivered daily sermons in support of the union.

In its best moments, organized labor unites the whole community in the fight. During the leadup to the 1934 Minneapolis Teamster Strike, Local 574 “got agreement for active support from Minneapolis unemployed organizations and the Farm Holiday Association, allied with the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party. On 15 May, Local 574, now 6,000 members strong, voted to strike all trucking employers, demanding union recognition, the right to represent inside workers, and wage increases.” By expanding our struggles, and supporters, outside of the workplace, we form a united front that strengthens all of us. In Oakland, we caught a glimpse of the revolutionary action such unity can catalyze with the occupation and transformation of Parker Elementary School. Our next step, as revolutionary workers, is to replicate, coordinate, and spread these collective struggles for industrial democracy far and wide.

That’s all for part eleven. Check back next week for part twelve, about how revolutionary unions can become an organized expression of working class autonomy from political parties, the state bureaucracy, and non-profits.

Hochschild, Adam. 2017. Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War. First. New York: Mariner Books. Pages 56-57.

Proletarians or Professionals?

This piece began as a research paper I created for a class that I took while working on my teacher certification in 2020. At first, it was meant to be a cut and dry, chronological history of the movement. I was working in-person for minimum wage at the height of the pandemic, so I was just trying to get it done. Common theme of my life up until then. Bu…

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Work in education? Get involved!

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get in front of an audience, get in touch! Check our post history to get a sense of what we are looking for, but we are open minded to all sorts of submissions.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

If you don’t have the capacity to get involved, we encourage you to share our work with other educators—especially your coworkers. For our readers who don’t work in education, please send our creations to any education workers you know.

Support Our Work

All our public work is freely available with no paywalls, and always will be. But if you want to help our collective cover the costs of hosting webpages, creating agitprop, and finding research materials, then please consider signing up for a paid subscription or donate to us on Ko-fi if you don’t want to give money to substack. With enough support, we can begin sharing the funds among collective members for them to use on various projects and pay others for any work they do for us—such as translating or printing materials.